(90s hardcore punk trajectory--diagram from Straight No Chaser #1)

I really hate the nostalgia industry that has engulfed hardcore punk over the last few years. American Hardcore, Stephen Blush's book and film, seemed rushed, homophobic, and fixated on violence while the flood of 90s hardcore reunions left me feeling equally empty about a period of time that meant a great deal to me. I haven't read Burning Fight or Radio Silence yet but I did contribute to a 90s DIY document that may or may not come out on AK Press. Part of me thinks that any overview of something as diffuse and undefined as a scene built by and for kids can never be fully captured. On the other hand I think it's crucial to have a hand in writing culture from the inside whenever possible. In any case, these are some thoughts I've been formulating on that time. (Questions by Mike McKee from Philadelphia.)

90s HC QUESTIONAIRE

--Please state your full name, age, occupation, and where you grew up / where you live now. --How would you describe your involvement in punk/hc throughout ’89-97? --Do you have a photo of yourself from this time period that you’d be willing to share and possibly have reprinted along with some of your responses?

Marty Roberts, age 34. I am an English Language Development (ELD) teacher, literacy coach, and school reform advocate. I grew up in Claremont, California, went to college in Santa Cruz and now live in San Francisco.

(Self-portrait, 1989)

How, when and where did you begin going to shows?

I’m no Jon Landau and it’s not 4 a.m. and raining, but I vividly remember being 27, thinking what it was like to be 17, and feeling old. At this moment I’m not hearing the future, but like Landau, “I never give up the search for sounds that can answer every impulse, consume all emotion, cleanse and purify—all things that we have no right to expect from even the greatest works of art but which we can occasionally derive from them.” Hardcore is and has been a visceral part of a bigger pursuit of authentic, passionate autonomous communities of passion and compassion.

I first really became aware of punk rock—or at least the outward signs of the punk underground—in 1985 at the Pipeline skatepark in Upland, CA. I was on a family vacation from Kansas where we were living at the time and I started noticing the Dead Kennedies and Black Flag logos that kids had drawn on their boards, jeans, and helmets. I remember distinctly connecting the graphic design of those logos with skate art of the time, the ollie holes in well-worn Vans, and the meditative hum of urethane. It wasn’t until ‘87/’88 when I moved to Claremont that I started seeing those subtle markers of the underground again, only by that time it was the Pillsbury Hard Core stickers that were stuck to the ceilings of El Roble Junior High and crude Jolt Hardcore (Paul “Frosty” Hertz from Chain of Strength’s early band) t-shirts a few outcasts wore.

(Half Man at Epicenter, SF, summer 94)

Claremont is about 40 miles east of Los Angeles, but it’s definitely not LA. It’s not Orange County and it’s not the high desert. It’s a college town suburb with one foot in the 60s counter-culture past and one in soulless contemporary suburban sprawl. Musically there have been times when a lot went on there. David Lindley and Ben Harper have called it home and the older brothers of my best friends at the time were in Man Is the Bastard and Chain of Strength respectively. Independent music, film, and art were everywhere and my friends and I devoured as much outsider sound as we could get our hands on.

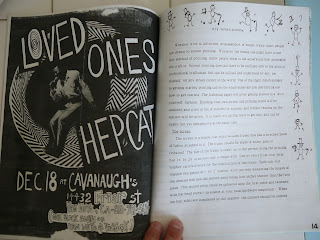

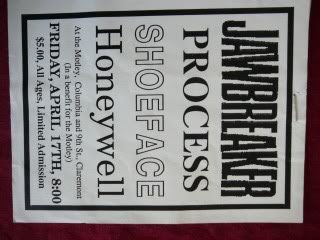

I saw a number of what would pass as punk bands around in 1989 and 90 but I really caught my stride by 1993 and started doing a zine called Straight No Chaser that was printed entirely on recycled show flyers. After three issues I called it quits, moved to Santa Cruz for college, published a book of flyer art from Southern California called Heavy on the Freak Sauce, and lived and breathed hardcore for the next several years.

(Honeywell 7" insert)

Between 1991 and 1999 I saw hundreds of great bands in many different spaces—Spanky’s Café in Riverside, The Toe Jam in Long Beach, Cell 63 out in badlands north of LA, basements and living rooms all over Santa Cruz (Third Street, Bixby House, California Street House), next to a stove in a guy’s kitchen in Rancho Cucamonga, a rapid transit stop at 24th and Mission in San Francisco.

(Drew and Chris of CAMPAIgN at Pitzer College, 1992)

How would you describe the landscape of the hardcore/punk scene as you saw it when you first started going to shows?

The anthropologist Clifford Geertz famously observed that culture was “the stories that they tell themselves about themselves”, and I think that’s a handy frame to think about the landscape of hardcore punk at the beginning of the 90s. The decentralized but interconnected scenes of DC, New York, LA, Boston, and the Midwest had been in development and reconstruction for ten years by the time my friends and I “discovered” hardcore. So much of what made punk punk had to do the ritual of the pit and not what was being said on or off the mic. For a kid-centered forum for countering alienation, rejecting convention, and challenging the norms of the above-ground, hardcore was feeling predictable and mundane. After ten years of foundation building there was enough to reject within punk as there was to embrace. The tough guy stance epitomized by Sick of It All and Agnostic Front, the fun-but-shallow lyrics of Gorilla Biscuits, and the once vital potential of a poison-free lifestyle lapsed into a caricature of pointed fingers, sportswear, and obligatory calls for unity as women and people of color were conspicuously absent were all “stories” that needed revision. Fugazi taking on stage-divers was, in my mind, as significant to the reshaping of narrative in the early 90s underground as Kent McKlard calling out Youth Brigade and Bad Religion in the Ebullition record inserts.

(Straight No Chaser #1)

What is the first thing that comes to mind when someone mentions “90s DIY hardcore?” ..or “90s HC” …or “94 core”?

Book-ended by underground expressions of anger and frustration, depression and self-analysis, the 1990s brought me into contact with remarkable people and showed me the power and potential of communities of resistance. At its best, hardcore helps young people find their own unique voice, not just emulate others. It was and is about rejecting excess, claiming space, discovering what you can make on your own. These are the characteristics that make hardcore more than music. I’m reminded of a poem by Michael Ryan that goes, “When the immutable accidents of birth/hometown, parentage, and the rest/no longer anchor this fiction of self and its incessant I me mine/then words won’t be like nerves in a stump crackling with messages that end up nowhere/and I’ll put on the wind like a gown of light linen/and go be a king in a field of weeds.” In many ways, hardcore has helped me do just that.

(Forever comp insert)

Do you feel like DIY hardcore in America throughout the early to mid 90s was different than the forms the culture had taken in the past or has taken since? -If so, how do you perceive or characterize it as uniquely different from other pockets or eras of punk/underground music?

Every generation has its touchstones to loathe. The 70s had Vietnam and Nixon. The 80s had Reagan and Thatcher. Kids in the 90s had Newt Gingrich’s “Contract With America”, Gulf War 1, a failed drug policy, and attacks on abortion clinics to make sense of. While the Zapatista uprising in Chiapas was inspiring, the dissolution of affirmative action and services for immigrants gave lie to the liberalism of California electoral politics and fueled the fire of those in the far-flung outposts of the subculture. At its best, hardcore spoke to issues, both political and personal, and proved itself more than just amplified adolescent ire.

(Old silk screen project)

Did it feel, at the time, as though you were witnessing and/or participating in the making of something new?

Truth be told, hardcore is only partially about tinnitus, sweat, and polemics against parent culture. It was—and still is—just as much about making zines, teaching friends to screen-print, learning to cook vegan and not just eat out at 7-11, and writing letters to folks in the far-flung outposts of the subculture. I did lots and lots of letter writing during that period. For ten years or so I really took seriously the art and craft of keeping up a correspondence with friends, many of whom I’ve never met but in some cases still talk to today. The advent of email around Y2K almost entirely cut out that process. I wasn’t steaming off stamps anymore, carefully folding flyers to share, and pouring myself whole-heartedly into the written word. Those letters extended some semblance of connectedness—community even—to me and dozens of others. What I didn’t have immediately available I created with pen pals and that, in part anyways, alleviated the sense of isolation and up-rooted or un-rooted-ness that was so prevalent at that time.

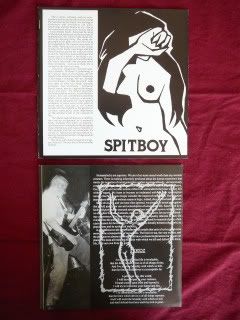

(Spitboy and Downcast 7"s)

Another key to that time was the realization that folks my age and slightly older had credible things to say about the world. Pouring over the writing in the Spitboy 12”, the Education comp, Rorschach’s Protestant—really influential records for that time—was what really set apart my experience of punk from what came before it. I’d always taken the time to memorize lyrics to sing at shows, but those records were really something to grapple with. I learned the word ‘egalitarian’ because of True Self Revealed and trotted it out in my junior English class (no kidding!) I can’t really say that of any record from before or many since.

(Coleman 7" insert)

Shows, bands, zines—at their best—were a combination of catharsis and self-exploration, and I’d say still are. I was raised in a Quaker family and even though I’ve considered myself an atheist for years there was something very familiar I found in some corners of the scene at that time. DIY echoed my childhood experiences of intentional community, potlucks, and handmade clothing. It was all there. Within Quaker meeting there’s this notion that the space that you share with other Friends is safe enough to speak one’s truth when the feeling is right. Rites of Spring put a name and voice those “transparent moments” but I got the sense that it was always there beneath the surface, waiting for the right synergy of heat and noise, risk and honesty. Whatever intangible thing it was that made it feel comfortable for people to take on their issues—privilege, body image, homophobia and sexism, personal trauma—in public was truly antithetical to all previous notions of what could and couldn’t be talked about in punk. Folks weren’t just trying to re-write “Rise Above” or live out the “hope I die before I get old” anthems of a previous generation’s rebel-rock spokesmen. The No Answers interview with Mike Judge that asked the last time Mike had cried seemed bold initially, but nothing in comparison to what people—especially women—were sharing about themselves in print and on the mic. I’ve always liked Jackie Kerzner’s (Coleman) comment that (hardcore punk) was “trying to exercise—or is it exorcise—the heavy clods which weigh us down.” People being swept up in the motion and emotion of shows and protests, sharing food and making zines with stolen copy keys at one in the morning—these were anti-slacker, anti-Generation X gestures that, yes, were pretty self-important and even comical to look back on, but they gave shape and purpose to the anger and anxiety that we were feeling at the time.

(Straight No Chaser #1)

The double-edged sword of that exploration was that as authentic as it could be it was almost immediately ritualized, codified, and commodified; turned into just another spectacle to be consumed. ‘Emo’ and ‘indie’ have become nothing more than marketing terms—in both the under- and above-ground—becoming synonymous with an aesthetic and not a practice. I’m really trying hard not to indulge in the over-used adjectives of the time, “crazy”, “brutal”, “amazing”, “political”, because the repetition of them really rendered them meaningless over time. In any case, an unfortunate aspect of such an insular community—maybe 20 core individuals within the 100 that might congregate regularly—is that the pressure to adhere to a set of heart-on-sleeve beliefs became as doctrinaire and as domineering as those rules that many of us were trying to cast off. Again, to reference Coleman, that line, “described not defined by the rules I obey” was something that we could have all taken to heart. This ethical rigidity had the effect of either driving some really good people away or forcing folks to say and do things that weren’t ultimately healthy or progressive. Pleasure became suspect; feelings were hurt. Friends stopped having the courage to disagree, finger-pointing returned, and hollowness set in. I don’t think that those are or were the values to found a community on let alone a start a revolution with.

What is your first, or your most distinct memory, of any/each of the following venues / show spaces?

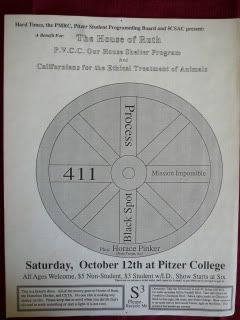

(Pitzer College flyer, 1992)

Best beginning-to-end show: Campaign (debut), Heroin, Spitboy, and Econochrist at Pitzer College, Claremont, 1992.

Best guest appearance: Chris Dodge singing “Blood Gutter” with Man Is the Bastard the night they played with Ruins (Japan) at Gilman, 1994.

Most idiosyncratic line-up: Tie: Floodgate with Chorus of Disapproval at a basement show in Simi Valley, summer 93, or Jone of Arc with MITB and UOA at the Jabberjaw, summer 94.

Best proof of Kent McClard’s sense of humor: The first-person Hardline commentary/confessional in Dave Mandel’s Indecision fanzine.

Oddest cover songs: Honeywell doing Outspoken’s “Survival” followed by the Beastie Boys’ “No Sleep Till Brooklyn”, Scripps College, Claremont, 1992.

Snarkiest recording: Fear of Smell compilation tie: Sam and Joe’s “Save the Fucking Children” routine v. Rich Oliver’s “Post-Everything”.

Best Sam McPheeters commentary: Dead tie—“No matter how many reggae songs you write about human rights, your audience will still ‘rock out’ and drink wine coolers” from Forever 7” compilation, or debating Sean Vegan Reich about masturbation in Dear Jesus.

Worst bathroom: Gilman.

Feel free to substitute any of the above venues for those more applicable to your geography in this time period.

I began speaking at shows at the first Torches to Rome show at the Third Street House in Santa Cruz, and continued speaking at shows for the next couple of years. I’ve got to give credit to Mike Kirsch for encouraging others to take up the mic, even interrupt his bands, to re-imagine the space of a punk show.

(Submission Hold house and friends, Vancouver, 1998)

When I helped drive on the Seein’ Red/Alfonsin/Bread and Circuits tour I’d speak on alternating nights with Monica Novarro (Mi Luna zine) and Rachel McLean (SF DOPE Project, Rachel zine) who were also traveling with the bands that summer. The hardest night was the first show of the tour in Seattle. I’d heard the name of a minor celebrity in the Seattle/SF graffiti/punk/skate scene, someone I knew mainly because he’d raped a very close friend and former lover of mine. I felt like my heart was jumping through my throat but still I found my way to the mic. This was about two years after the Chris and Dana letters in HeartAttack and one year after the controversy surrounding Jux and Punks With Presses in the East Bay. There would have been support for a witch-hunt but that wasn’t the approach I was looking for. In those moments I was processing the juxtaposition of what I felt with what would help my friend heal, and while some folks may have thought that I took the safe route by not outing the rapist, I needed to use that time to think of her and not myself.

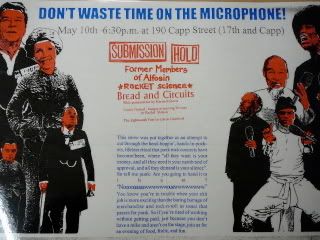

(Submission Hold, Bread and Circuits, Rocket Science at 17th and Capp, spring 1998)

The other show that stands out in my mind was a night of art, food, and music at a live-work space at 17th and Capp in the San Francisco’s Mission District. Between each band artwork was shown and shared along with food. I gave a slideshow called “A Traffic in Suffering” that was based on work I’d done on photographic images of violence and pain. While it went on too long and at times probably felt a bit like a college lecture, I’m pretty sure it was one of the first times since Pictures of Starving Children Sell Records that someone had challenged the decontextualized spectacle of pain and suffering. Carrie Crawford (Cat Planet, Dog Star zine) had created a multi-media installation about her complicated relationship with family, and Rachel McLean deconstructed mass-media representations of anorexia from fashion magazines. It was a unique, unprecedented night that sadly was also unrepeated. One of the few tangible outcomes of that night was that Todd Regelado took inspiration from the grass-roots food distribution network that operated out of 17th and Capp to co-found the Los Angeles Burrito Project. Over a decade later you’d never suspect that that space existed, but now thousands of burritos are made monthly and handed out, free of charge, to homeless families on the streets of Los Angeles.

(Alex and Butch from Former Members of Alfonsin in Seattle, 1998)

In retrospect, these are the sorts of moments that get eulogized as emblematic of the decade as if it couldn’t happen again or couldn’t happen now. What I find disappointing is the lack of imagination that hardcore kids over 30 show when they lionize the past but don’t reinvent their present. I simply reject the notion that something is gone that can never be recaptured. It’s not the case that something was stolen from us. We gave away just as much.

(Chuck reading at the first Bread and Circuits show, Berkeley, 1998)

What was the first fest you attended? -how did you travel there? -where and with whom did you stay?

The only fest I went to was the second Goleta Fest at the tail end of my travels with Bread and Circuits and others. No offense, but I hate huge shows. After driving down the coast from Vancouver to Seattle, through Roseberg to Berkeley, then onto Goleta I was in no mood to hear 35 bands doing their best Noothgrush interpretation. I slept on a couch in the main hall and woke up for Slave One, played some soccer with some nice kids from back east, ate too much bread and hummus, and slid into a grimy sleeping bag at Lisa Ogelsby’s apartment. I’d been going to shows for almost ten years at that point and the excitement of a show was really starting to wear off.

(Born Against insert in the Forever comp)

I did sit in on the gender discussion that some folks organized, but it really struck me as a nervous approximation of some discussion that’d taken place in Columbus earlier that summer. I wasn’t at that earlier and I don’t mean anyone any disrespect but there was such a conscious effort to anchor the discussion in “frameworks” and “reference points” that it didn’t feel as much like a conversation as it did a lo-fi liberal arts college lecture. It’s a lot to put on people to always be “on”, to always be “right” and I sensed that in the room. Some people were really forthcoming and others just listened, as it should be. It was just too large a group in too loud a space with too little time, and ultimately tough conversations need time. Time to digest, time to reflect, time to question, which really drives home the need to create community on something other than the limited interaction of a show. Working now with teens in a school where I have 180 days a year to develop relationships and foster exchange and debate paints my earlier punk experiences in stark relief. Looking back I really have to question how much community there really was. Clearly it meant the world to a lot of us at the time but I’m not sure that I grew any closer to anyone just because of the space we shared. If anything, touring made me realize how little I really had in common with so many people in the greater scene.

(Cyclops 7")

Do you feel like there was a particular style or “look” that defined this pocket of culture?

If I could sum up a look of a decade it’d be something like this: sunken cheeks, bad posture, fallen arches and a backpack. It’s up for interpretation what all that meant. Did that sweater-vest signify some kind of emotional sincerity or was there always a cool breeze blowing where Frail came from? Were those black Chuck Taylors a quiet protest against American cultural hegemony or a way of proving that it’s hip to be square? Were the choker bead necklaces that were so prevalent a tribute to the marketing prowess of the 1993 Shelter/108 tour? Or were they a way of saying that the constricting beads were like the rules—straight edge, veganism—we’d willfully adopted to constrain, yes, but also define, ourselves? I wonder how large an effect national zines like HeartAttack had in both reflecting and directing the fashion sense of the times. What’s interesting to me is how quickly DIY went from referring to a form of production to an aesthetic.

(Rorschach, from the re-issue of Protestant)

Do you attribute any portion of your politicization to your experiences in hardcore?

A friend of mine used to joke that “outspoken is just a band”. Hardcore definitely introduced me to some extraordinary people and challenged me socially, but it’d be self-indulgent and more than a little bit revisionist to say that everything I did in hardcore was political. Hardcore is an add-on, an accessory. It’s the (by)product of those with enough time, money, and headspace to attend to things beyond day-in, day-out survival. I think my politicization was facilitated by hardcore but not responsible for it.

I was lucky enough to come of age in two very different communities simultaneously. The first is rock climbing, which literally took me into a wilderness away from home and allowed me to explore the limits of my fear and fitness. Its emphasis on mutual trust and doing the most (the hardest route, longest face, highest peak) with the least (gear, impact, support) shaped a significant part of my worldview. Hardcore, on the other hand is almost entirely an indoor phenomenon, put me in a position of creating a new home—an adopted family—with like-minded individuals who were challenging the tenets of American mass culture. At 34 I’m now more interested in creating community more around the values I embrace than those I reject. It’s risky to write a writes a biography that radicalizes the liberal and elevates the mundane gesture to era-defining manifesto, but that’s what all too often happens in this scene. I will say that much of what passed as political discourse in 90s hardcore was far from making punk a viable threat to established orthodoxies and institutions. How is the political configured? How much was really being said at that time and how much was deemed radical by context alone? I still don’t hear a threat in the A-list of the 90s—Antioch Arrow, Amber Inn, (ordination of) Aaron. This isn’t to say that the music and efforts of individuals at that time weren’t important—they were. However, there’s a big difference between what matters and what makes change.

(Jose/Bread and Circuits in SF, 1998)

In terms of my own political development, Columbine—April 20, 1999—marks a clear turning point from my involvement within hardcore to the work I’ve taken up, through teaching, outside of the underground. While I was shocked by the events of that day I can’t say I was surprised. Those boy’s actions were an extreme expression of an alienation and self-loathing that any number of friends and I experienced throughout the decade. It was by identifying with their angst that I felt I needed to counter the forces that led them to harm others and in the end, take their own lives.

(Born Against insert to the Forever comp.)

I took from hardcore the importance of developing one’s passions free of the market, on one hand, and the need for an attentive eye toward sustainability, on the other. Being engaged in a community where young people defined their own standards of success was liberating and instructive at the same time. Nothing motivates like feeling authentic ownership in any process, and I’ve taken that into the classroom. What I think holds back punk-based activism is our uncomfortable relationship with leadership and autonomy. So much energy is spent ridiculing the hierarchies that we resent—which is important in its own right—that we often haven’t developed the confidence to name our issues and take concrete steps to impact them. I think the scene still looks to bands to shape political discourse and the show is still the primary venue for that exchange. What I’ve come to realize is that time is the most elusive resource for agents of change. Likewise, DIY has reinforced a narrative that places the individual, not the collective, at the center of the universe, which ironically is the same worldview espoused by would-be Reaganites. The equity-centered reform efforts that I’m currently part of are deeply informed by hardcore but have felt equal influence from principles of intentional listening in co-constructed spaces with allies from divergent backgrounds and perspectives. Being fully present in the moment, meeting people where they are at, assuming positive intent, and withholding judgment are now part of my practice as a reform leader in my field, but those were not necessarily what I learned from within our scene. It took leaving hardcore to develop this skill set. Ultimately, it was a sacrifice worth making.

(Rorschach from Protestant re-issue)

How and when did you learn about riot grrl?

I’m far from qualified to speak about riot grrl but I will say this: Riot grrl was a necessary reaction to the underlying inequities in values, rituals, and language of hardcore punk and the mainstream culture that gave birth to it. Creating women-specific spaces was/is critical to unpacking and interrogating the ways in which half the population is systematically devalued in ways both explicit and implicit. What I know was problematic about riot grrl at the time was that while reclaiming girl-hood was important, so too was (or would have been) finding ways to recreate and re-envision what it meant to be a woman. For that reason, I saw more women find themselves outside riot grrl than inside it.

(Still Life and Dawn Williams interview in Straight No Chaser/Fulcrum #2)

People (thoughts, impressions; no gossip)

Chris Jensen

Chris went to Pomona College at the same time I was in high school was the logical bridge between the two “eras”. He’d grown up with guys in Krakdown, did abortion clinic defense during the Operation Rescue attacks in the summer of 92, and had the drive to book shows on campus, and record with Campaign all while getting his degree. I can’t communicate how influential he was at that time. He didn’t stage-dive but he also never lectured. He was outspoken at shows when others were silent, and yet was always very approachable. And the Hard Times radio show on KSPC was deliberately trying to challenge the notion that hardcore was just fast music. That was the first place we heard a lot of bands that didn’t fit the molds of the old punk canon. Chris was in that first wave of hardcore people who took up teaching as a way to make real a commitment to one’s beliefs—to literally campaign for what one valued—and his articles in HeartAttack had a profound influence on those who would follow in his wake.

(Cheap Guy Music flyer, Riverside, 1991)

Eric Wood/MITB

“Sheky”, as Eric was known around Claremont, is a character of unparalleled intensity. Anyone who’s ever seen his focus while pouring a latte or heard him hold court on the merits of early Scorpions, Eno’s early ambient records, or the latest throat-punishing vocalist from Japan knows this. What gets lost in the buzz around his micro-celebrity is his genuine, caring, at times insecure side. I never felt like I fully knew the man but I’m glad that I got to see more dimensions to him than just that the guy who calling for secular jihad against Thomas Lenz.

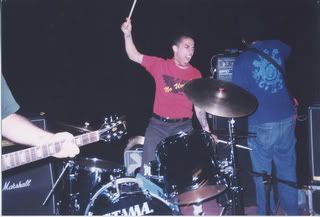

Henry Barnes with MITB at Scripps College, spring 93. From Straight No Chaser #1.

Henry Barnes/AFC

When I first met Henry he was also working baking shifts at Some Crust Bakery along with Eric Wood and later Drew Gilbert (Floodgate/Fisticuffs Bluff). He was one of the many gifted Barnes children who grew up in Claremont. His father, Richard “Dickie” Barnes, was an esteemed professor and poet in town, and his younger brother Rufie were in school together. Rufie shape-shifted himself through many sub-cultural identities in the 90s and during his straight edge phase he was caught on film, shouting along to Chain of Strength in The Unheard Music. Henry, though, always followed his own muse and crafted the instruments to make real the songs he heard in his head. My final year of college I approached him with the idea of doing a recording based on the myth of the phoenix. We discussed it extensively and I created artwork for a 7” that never came out in that form but was included on the Thorny Path 12”. What I love about Henry is his individuality, earnest demeanor, limitless creativity, and willingness to struggle through the lean times in order to get closer to his own personal ideal for living.

(Barnes' DIY guitar pedal schematic from Straight No Chaser/Fulcrum #2)

Excessive ephemera:

(Scripps College flyer, 1992)

(Che Cafe flyer, 1991)

(A flyer I made for a 17th and Capp show)

(Straight No Chaser #1)

(Pitzer College flyer, 1992)

(Suicide prevention flyer I made when I began teaching full time)

(Top and bottom--rape prevention flyer I made in high school, 1993)

5 comments:

marty, i cant believe i ran across this...i got linked here from another blog.

i did mckee little q & a last year as well...spent along time with it, i hope the book materializes at some point. he told me he was gonna have it wrapped up last summer and when i asked him about it a few weeks ago i got...silence.

--isreal

excuse my errors of syntax...the kid was kicking me as i was trying to type.

I too did the McKee Q & A... offered to talk more with him to no avail (so far). Never thought of posting my responses though.

What were the Chris and Dana letters in HeartAttack? I read it at the time, but don't remember. I do remember the Jux controversy.

It’s odd to me how there’s not more about Jux on the internet. He was a serial child molester and an integral part of the East bay scene. I’m amazed how the East bay punk (Kamala; eggplant; etc) elite effectively kept their credibility after taking Jux’s side. Every few months, I look for more Jux stories. It’s really sad how many lives were ruined at the punk with presses warehouse.

Post a Comment